the Sierra Nevada

California

September 2016

Whitney Portal Road. One road connects Whitney Portal to the rest of the world, the town of Lone Pine in particular. This 11.7-mile stretch from trailhead back down to South Main Street in Lone Pine is a relatively straightforward road with a few twists. And who doesn’t like a few twists!

This environment, subject to the freeze/thaw cycle of the High Sierra seasons, is challenging to the integrity of a vehicle road. Run two-ton vehicles up and back and the road will crinkle, rut and break, growing worse the longer it goes. The mountain overlords, or at least the road masters, chose this summer to repair and repave the road.

“The road is closed from eight until eleven each morning,” the emotionless ranger told me on the telephone before our trip, “and from one to four in the afternoon.” I try not to be judgmental about his lack of feeling while relating this information, the most important piece of data I need to know about our hike: can we actually get there? After all, the ranger probably speaks these words a few thousand times each day, and listens to a few thousand of us hikers bitch about the inconvenience. He should be more friendly.

“And there are periodic half-hour, unannounced closures too,” he adds. Well, that one puts me over the top. No it doesn’t.

It’s past 4 p.m. We expect smooth sailing back to town. Smooth sailing in our cars. We get smooth sailing for several miles until a portly gentleman dressed in a reflective vest wanders out on the road in front of us, idly manhandling a portable stop sign. He props it up on the road and turns it to face us. It is painted with the unmistakable word STOP in white letters in an octagonal field of red outlined with a white border.

We stop. Soon enough, more than a dozen cars accumulate behind us on the road, all stopped. “What’s up?”

Road Crew Guy explains that this is an unexpected delay. We know this. “The brakes on one of our electrical trucks caught fire and he crashed right at the bridge.” We didn’t know this.

4300 feet of downhill. Without brakes, you could probably get up to 600 miles per hour. Brakes catching fire on this slope doesn’t surprise me. It does surprise me that he tells us that this guy burned out and crashed. Inconsiderate of the driver to block the road. We had to wait for them to clear the wreckage.

After an hour or so, one lane opens and we are let through. Portly Guy with the vest dragged his stop sign off the road and sat down in his folding lawn chair as we paraded past.

Down the mountain, instead of seeing the accident, the road that was blocked is now closed. We are rerouted south and west onto a road that, likely, none of us motorists have ever seen before. Crewmen are standing around wearing their National School Bus Glossy Yellow* vests. As the driver, Lisa leans out the window and asks a NSBGY guy about the detour. “Take this road and turn left on Sunset Drive. If you have any problems, just ask the locals.”

* National School Bus Glossy Yellow is actually the official name of this particular bright, reflective color. Most of the time we just call it, “yellow,” or if we have the time, “bright yellow.”

In unfamiliar territory, we turn left onto Sunset Drive and in exactly two blocks, Sunset Drive ends. I’m thinking, “Ask the locals? What locals? Knock on someone’s door?” There are a few houses here, a few doors too, but no locals.

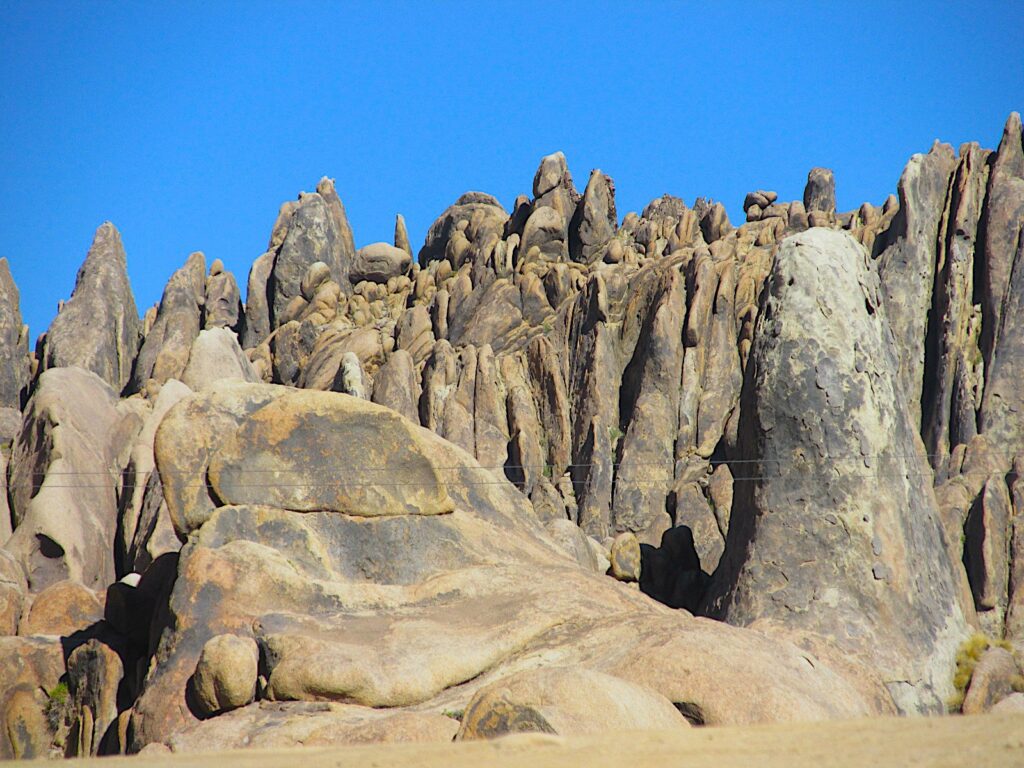

Lisa makes random turns through what appears to be an alien landscape. Our very twisty road takes us through formations that I’ve heard described as Buttermilk rocks. I can’t find the name of this narrow two-lane road but part of it parallels Tuttle Creek. I’m guessing Tuttle Creek Road.

Full disclosure. Lisa has her phone with her and she asks Siri for directions. Siri responds with the electronic, cyberspace equivalent of saying, “Lisa, I have no friggin’ idea what you are talking about.” Still an inveterate fan of maps, even when I don’t have one, I am quietly pleased.

Part of this area is BLM land, the Bureau of Land Management, whose self-stated mission is “to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of America’s public lands for the use and enjoyment of present and future generations.”

As far as this ten-minute jaunt on their land is concerned, the BLM has the enjoyment part down. It’s primitive landscape, smooth mounds of brown rock piled up in fascinating patterns, looking like a pile of potatoes, alternating with rugged, lava-like stone fins reminding me of the condenser on the back of a room air conditioner. The road is amazingly clear: no stones or scree at all, cleaner than my living room. Still, I find myself involuntarily ducking as we go around some tight turns with overhanging rock.

Confident that eventually, we’ll find something familiar, like the town of Lone Pine, we drive on in this beautiful, strange country.

Tuttle Creek Road takes us back to the main highway, Whitney Portal Road. We make a right turn and within moments we’re back in town and at our hotel.

This little chain lodge has a heated whirlpool. Other than massage, the greatest invention in the world to loosen up overworked muscles. This is one of the good parts of life: lying in the foaming hot water of the outdoor pool with a clear view of the open Mount Whitney sky.

But wait, we still have an issue. What do we do to dispose of the spent or partially used fuel canisters after our hike? We haven’t made enough meals to have used all the fuel in our can. You can’t just chuck these things into the trash. They can explode and some people get bothered when that happens. It’s one of the reasons the TSA doesn’t want to carry your can on their airships. Manufacturers recommend that you burn off all the fuel from the can and puncture it. Then they advise to “dispose of your fuel canister properly, according to local ordinances.”

That’s not always easy to do on a trip to a strange land. How do you even find out what the local ordinances are? Often, coming out of the wilderness, you just don’t have time to go through all that business and still be on time for your flight home. I thought that maybe the gear store where we bought the can would be willing to recycle it for us. Nope. They don’t do that.

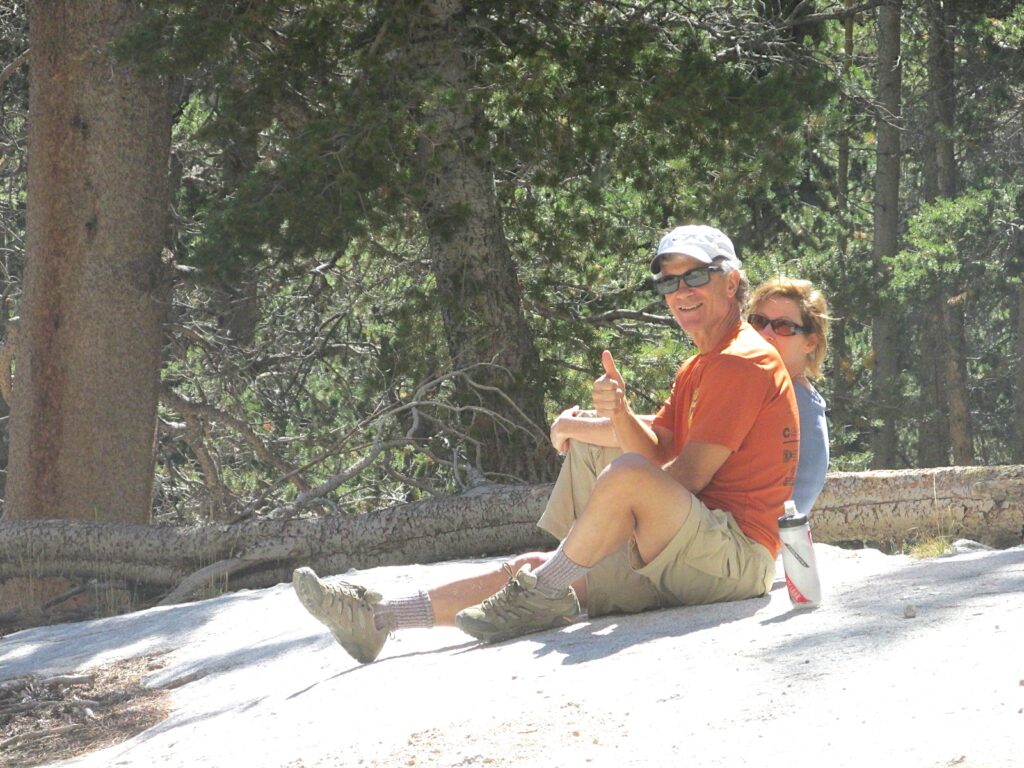

On our last morning, Lisa and I are having a delightful breakfast at an outside table of our hotel, Mount Whitney looming over us in the western distance. We notice a couple and their two daughters loading up their vehicle with backpacks and all the gear that goes with them. On a hunch, I approach the group and ask if they need any stove fuel. Lisa and I took two with us on our trip, one for backup, and still have a lot of fuel left over. The guy says, “Probably. Let me take a look at them to see if they will work with what we have.”

I run into the building to our room and return with the two cans. While I was doing that, he told Lisa their itinerary: a four-day trip through the high Sierras. We just got off the mountain and already we’re envious.

Anyway, the cans are a fit for their stove and he happily accepts our two fuel cans. He asks, “What do we owe you?” We say, “In return, you have to have a great time on the trail.”

As he leaves, I tell him, “You are already doing us a favor. If I were to try to take these cans on the airplane, I would be sure to give you a call in twenty years when I get out of prison. Y’know, to see how your trip went.”